What might your perceived risk of death by transport accident have to do with your motivation to eat healthily? Well, potentially, the two are causally linked. Indeed, our motivation to look after our health may well be affected by the overall level of risk we face, and that’s something I’ve spent a great deal of time thinking about over the past decade or so. The link could have big implications for how we think about health behaviour. However, my work on this (in collaboration with my excellent colleagues) has only really been published in academic journals, where powerful ideas can be obscured by the necessary details and caveats that must be made in scientific reports. Time to attempt a non-academic explanation!

Who cares about changing health behaviour?

To start, I’ll point out that a good deal of effort is being poured into attempts to understand and change behaviour. Behavioural insights and nudging approaches have become increasingly popular in the health sector, and beyond. Endeavours range from nudging people to use greener energy to changing their online purchasing patterns, and everything in between. In some cases, these attempts have been very successful (automatic pensions enrolments, to give one example). Yet, changing health behaviour remains difficult. This matters because, non-communicable diseases, which are generally driven by lifestyle, are a huge global health challenge.

A popular model in the health behaviour change world is the COM-B model. COM-B stands for Capability, Opportunity, Motivation – Behaviour. As you might expect, the framework suggests that behaviour will be affected by the other three factors of capability, opportunity, and motivation. What I’m about to explain is something which I believe to be one of the “hidden” forces affecting people’s motivation to look after their health. To some extent, it is hidden in plain sight because, once I explain this idea to people, they tend to agree that it’s kind-of obvious. And yet, I believe it is the reason that many efforts to change health behaviour fail, or even widen inequalities*.

*Also see here for an excellent explanation of the important role of agency in the success of population interventions. This is a related, but subtly different, reason that some well-intentioned interventions have turned out to be inequitable.

Perceived uncontrollable risks and health behaviour

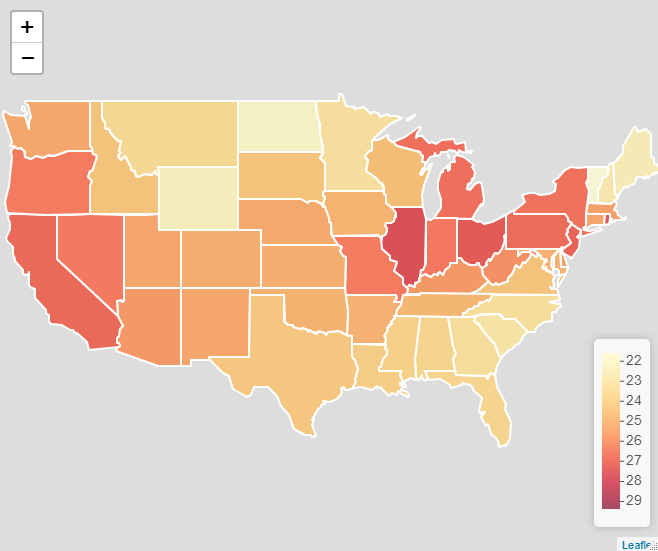

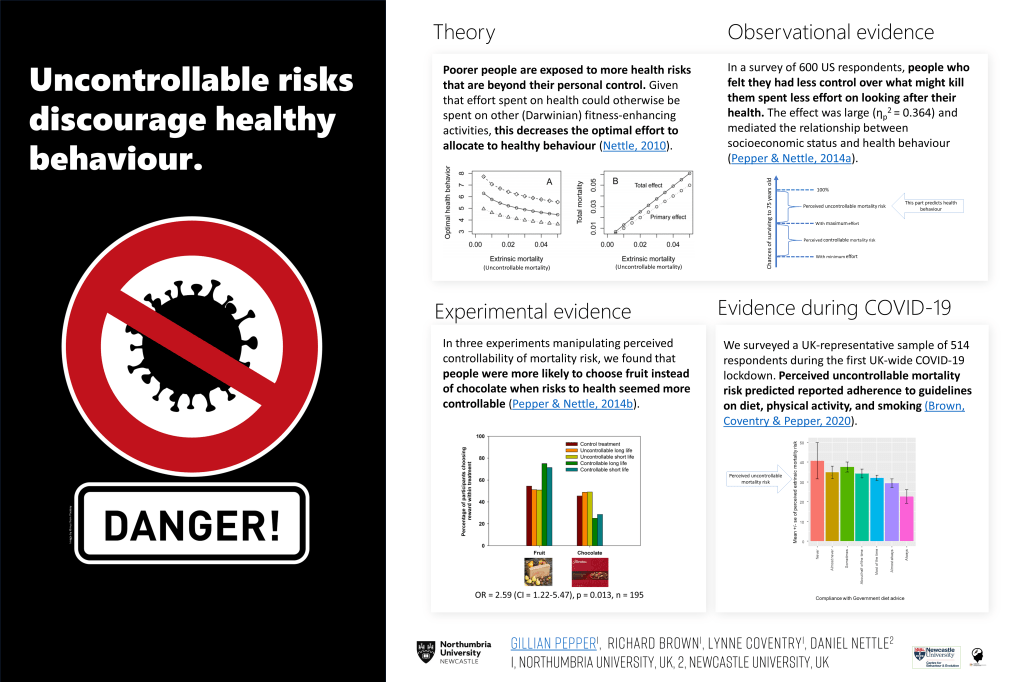

So, what is this “hidden” force affecting our motivation to look after our health? Put simply, it’s the extent to which we expect our efforts to pay off in the long run. We all face a variety of health and safety risks on a daily basis. Yet, for some, these risks are more numerous, more serious, or harder to avoid. Imagine, for example, living in a rented apartment that you know to be unsafe. The flammable cladding hasn’t been replaced, and the boiler is broken more often than it works. You suspect it’s probably leaking. Your building is in a polluted neighbourhood, where road accidents are common. Crime and interpersonal violence are rife in this area, so you don’t feel safe, but you can’t afford to live anywhere else. People in your neighbourhood regularly die young. In a context like this, do you think you would worry about eating 5 portions of fruit and vegetables a day? Would you worry about whether you’d got your daily step count in? Not so much, I expect. You would have bigger worries and, even if you had the best possible diet and exercise routine, you won’t necessarily live to see the benefits. This is the basis of the Uncontrollable Mortality Risk hypothesis, which was drawn from a behavioural ecological model by Daniel Nettle. Daniel’s work explains that people of lower social class tend to be more exposed to a variety of health risks, which they generally find harder to avoid. In response to this, his model suggests, they will tend to reduce their levels of preventative health behaviour. The compound effect of this is a widening of the gap: initial health inequalities affect health behaviour, leading to increased inequalities. The idea doesn’t just help us to understand class inequalities. It can help us to understand variation in health behaviour more generally. Anyone who feels that they face unavoidable risks to their health and safety, regardless of social class, should be less motivated to take care of their health. This has some interesting implications for future research. For example, it means we should expect differences in health behaviours based on levels of risk in different environments. This indicates that certain research approaches, such as geospatial analyses mapping environmental risks onto health behaviours could be fruitful. Indeed, the hazards I described in the example above, were imagined in a UK context, and the UK is, in global terms, a relatively safe place. In other countries, challenges such as war, terrorism, violence, extremes of temperatures, and natural disaster risk likely outstrip most other health and survival concerns.

The double dividend of safety

There are many interesting implications of the idea I’ve described so far, some of which are discussed in our academic publications on the subject (see below). However, I want to emphasize one key concept: The double dividend of safety. The double dividend of safety is simply the idea that, if we make people safer, by reducing those risks which they can’t avoid for themselves, we can expect a spontaneous improvement in their motivation to take care of their own health. So, we get the primary benefit of the initial improvement in safety, and the additional, secondary benefit of improved health behaviour.

Understanding the double dividend of safety is important for numerous reasons. Among them, is the fact that public health goals are often approached in silos. Behaviour-change programmes operate in isolation, with practitioners rarely able to address the wider problems affecting those whom they seek to serve. This is not news, of course. Healthcare leaders have pointed out the need to break down this siloed approach. However, the double dividend of safety gives us another reason to call for joined-up thinking. It also emphasises the need to get the basics right. Addressing key challenges such as housing quality, crime, traffic safety and pollution, may turn out to be far more beneficial than a dozen behaviour change campaigns when it comes to reducing health inequalities.

For those who want to see the academic papers:

Pepper, G.V. & Nettle, D. (2014) Perceived extrinsic mortality risk and health behaviour: Testing a behavioural ecological model. Human Nature 25(3) [Article]

Pepper, G.V. & Nettle, D. (2014). Socioeconomic disparities in health behaviour: An evolutionary perspective. In D. W. Lawson & M. Gibson (Eds.), Applied Evolutionary Anthropology: Darwinian Approaches to Contemporary World Issues. Springer. [View]

Pepper, G.V. & Nettle, D. (2014) Out of control mortality matters: the effect of perceived extrinsic mortality risk on a health-related decision. PeerJ 2:e459 [PDF]

Pepper, G.V. & Nettle, D. (2017) The Behavioural Constellation of Deprivation: Causes and consequences. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 40 (e346)[Link]

Pepper, G.V. & Nettle, D. (2017) Strengths, altered investment, risk management, and other elaborations on the behavioural constellation of deprivation. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 40 (e346) [Link]

Brown, R.D., Coventry, L., & Pepper, G.V. (2021). COVID-19: the relationship between perceptions of risk and behaviours during lockdown. Journal of Public Health. [Link]

Brown, R.D., Sillence E., & G.V. Pepper (2022) A qualitative study of perceptions of control over potential causes of death and the sources of information that inform perceptions of risk. Health psychology and behavioral medicine 10 (1), 632-654. [Link]

Brown, R.D., Sillence, E., & Pepper, G.V. (2023). Perceptions of control over different causes of death and the accuracy of risk estimations. Journal of Public Health. [Link]

Brown, R.D., Sillence, E., & Pepper, G.V. (2023). Individual Characteristics Associated with Perceptions of Control Over Mortality Risk and Determinants of Health Effort. Risk Analysis. [Link]

Brown, R.D., Sillence, E., & Pepper, G.V. (2023). Perceptions of control over different causes of death and the accuracy of risk estimations. Journal of Public Health. [Link]

Click here for a short guide to measuring perceived uncontrollability mortality risk, and here for an explainer video by Richard Brown.

learned a vast amount in my first few weeks. I have witnessed a small team with a large portfolio, doing some heroic work. They deal with everything from the classic issues such as obesity, sexual health, smoking, and alcohol and drug use, to wider determinants of health including active transport, pollution and parks. They juggle the local politics of councillors, which can require a short-medium term outlook, with the priorities of Public Health, which are necessarily long term ones. All of this is done in the context of budget cuts and increased pressure from seasonal issues such as flu, and novel concerns such as Ebola. No easy task.

learned a vast amount in my first few weeks. I have witnessed a small team with a large portfolio, doing some heroic work. They deal with everything from the classic issues such as obesity, sexual health, smoking, and alcohol and drug use, to wider determinants of health including active transport, pollution and parks. They juggle the local politics of councillors, which can require a short-medium term outlook, with the priorities of Public Health, which are necessarily long term ones. All of this is done in the context of budget cuts and increased pressure from seasonal issues such as flu, and novel concerns such as Ebola. No easy task.